Marker Interfaces Are Not Evil

September 08, 2022—At least, not necessarily (programming)

When I Google “marker interfaces are bad” then the article “Marker Interfaces Are Evil” is close to the top.

Well, are they?

I don’t think so. Let me explain why.

Marker interfaces reveal intent

Imagine you have a report rendering system:

public class ReportRenderer

{

readonly IReadOnlyDictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer> _renderers;

public ReportRenderer(IReadOnlyDictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer> renderers)

{

_renderers = renderers;

}

public Report Render(IReportModel model)

{

var modelType = model.GetType();

if (_renderers.TryGetValue(modelType, out var specificRenderer))

return specificRenderer.Render(model, this);

else

throw new Exception($"No renderer available for models of type {modelType.Name}");

}

}

public interface ISpecificReportRenderer

{

Report Render(IReportModel model, ReportRenderer generalRenderer);

}

public abstract class SpecificReportRenderer<T> : ISpecificReportRenderer

where T : IReportModel

{

protected abstract Report Render(T model, ReportRenderer generalRenderer);

public Report Render(IReportModel model, ReportRenderer generalRenderer)

{

if (model is not T asT)

throw new Exception("Mismatched types");

return Render(asT, generalRenderer);

}

}

public interface IReportModel

{

// Look, ma! No members!

}

public class Report

{

... // Pretend there's stuff in this Report class, like a tree of WPF controls or something

}

Here’s how you might use it:

var renderers = new Dictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer>

{

[typeof(StringReportModel)] = new StringReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(DoubleReportModel)] = new DoubleReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(TableReportModel)] = new TableReportModelRenderer()

};

var renderer = new ReportRenderer(renderers);

var report = renderer.Render(new TableReportModel

{

Title = new StringReportModel("Billy Bob's finances"),

Rows = new IReportModel[][]

{

new IReportModel[]

{

new StringReportModel("Date"),

new StringReportModel("Location"),

new StringReportModel("Amount")

},

new IReportModel[]

{

new StringReportModel("2022-09-08"),

new StringReportModel("Somewhere in the world"),

new DoubleReportModel(100.0)

}

}

});

// Now you have a rendered report!

Of course you can always use it like this, too:

var report = renderer.Render(new StringReportModel("Hello, world!"));

…or like this:

var report = renderer.Render(new DoubleReportModel(42.0));

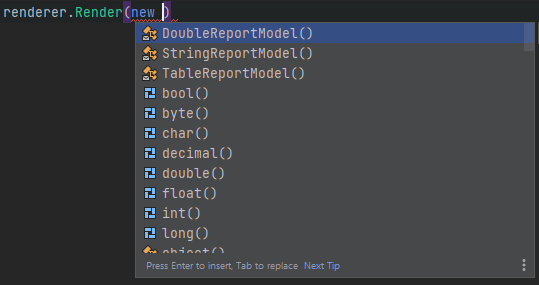

And of course any IDE more sophisticated than Notepad will give you autocomplete like this:

Do you notice how the IDE front-loaded the various report models in that list? Want to guess how the IDE inferred your intent?

And look what happens when I try to generate a report from a Logger:

renderer.Render(new Logger());

// ^^^^^^ [CS1503] Argument 1: cannot convert from 'Logger' to 'IReportModel'

Want to guess how the compiler knew that it was improper to generate a report

from a Logger?

If you guessed that the marker interface revealed intent then you’re correct!

The (supposed) alternative

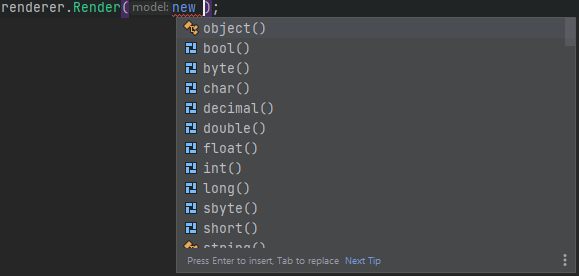

Imagine what would happen if ReportRenderer.Render() accepted object:

public class ReportRenderer

{

readonly IReadOnlyDictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer> _renderers;

public ReportRenderer(IReadOnlyDictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer> renderers)

{

_renderers = renderers;

}

public Report Render(object model)

{

var modelType = model.GetType();

if (_renderers.TryGetValue(modelType, out var specificRenderer))

return specificRenderer.Render(model, this);

else

throw new Exception($"No renderer available for models of type {modelType.Name}");

}

}

public interface ISpecificReportRenderer

{

Report Render(object model, ReportRenderer generalRenderer);

}

renderer.Render(new Logger());

// No compile errors

I think marker interfaces improve this situation.

Marker interfaces make abstractions possible for coding evil

Sometimes in C# you just have to use reflection and opaque type casting because C#’s type system is so limited. And when you do, it’s nice to be able to have some kind of abstraction available. In those situations a marker interface can help.

A good example is my report generator above. Compare it to this alternative that doesn’t require reflection or type casting:

public interface IReportModel

{

Report Render();

}

public class StringReportModel : IReportModel

{

public string Value { get; }

public StringReportModel(string value)

{

Value = value;

}

public Report Render() => new ... // Use your imagination

}

public class TableReportModel : IReportModel

{

public StringReportModel Title { get; init; }

public IReportModel[][] Rows { get; init; }

public Report Render()

{

var report = new Report();

report.Add(Title.Render());

foreach (var row in Rows)

{

var rowReport = new Report();

foreach (var cell in row)

{

rowReport.Add(cell.Render());

}

report.Add(rowReport);

}

return report;

}

}

What did we have to do to attain this so-called paradise? We:

- Threw out the

ReportRenderer - Made each model responsible for rendering itself

It’s always a good day when I get to throw out a class because that means there’s less code to maintain.

But is it a good day when classes gain an extra responsibility? What will we do

when we want to render the models into CSV text instead of whatever Report is?

As the code above stands you’d have to rewrite all the models. I don’t think it

makes sense to change models to suit the presentation layer.

That should clue us into the fact that the various report models now have too much responsibility. Here’s one way to refactor that:

public interface IReportModelRenderer<T>

{

Report Render(T model);

}

public class StringReportModel

{

public string Value { get; }

public StringReportModel(string value)

{

Value = value;

}

}

public class StringReportModelRenderer : IReportModelRenderer<StringReportModel>

{

public Report Render(StringReportModel model) => new ... // Use your imagination

}

public class TableReportModel

{

public StringReportModel Title { get; init; }

public ???[][] Rows { get; init; }

}

public class TableReportModelRenderer : IReportModelRenderer<TableReportModel>

{

readonly IReportModelRenderer<StringReportModel> _stringRenderer;

readonly IReportModelRenderer<???> _cellRenderer;

public Report Render(TableReportModel model)

{

var report = new Report();

report.Add(_stringRenderer.Render(model.Title));

foreach (var row in model.Rows)

{

var rowReport = new Report();

foreach (var cell in row)

{

rowReport.Add(_cellRenderer.Render(cell));

}

report.Add(rowReport);

}

return report;

}

}

But what type should I specify for the TableReportModel.Rows array? And what

type parameter do I give for TableReportModelRenderer._cellRenderer?

I only see two choices: object, or a marker interface. And if I pick object

then I lose IDE autocomplete and can also write nonsense code that tries to

generate a Report from a Logger.

So guess what the better answer is?

Integrations don’t have to be hard with marker interfaces

Let’s go back to my original report generator code toward the top:

var renderers = new Dictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer>

{

[typeof(StringReportModel)] = new StringReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(DoubleReportModel)] = new DoubleReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(TableReportModel)] = new TableReportModelRenderer()

};

var renderer = new ReportRenderer(renderers);

var report = renderer.Render(new TableReportModel

{

Title = new StringReportModel("Billy Bob's finances"),

Rows = new IReportModel[][]

{

new IReportModel[]

{

new StringReportModel("Date"),

new StringReportModel("Location"),

new StringReportModel("Amount")

},

new IReportModel[]

{

new StringReportModel("2022-09-08"),

new StringReportModel("Somewhere in the world"),

new DoubleReportModel(100.0)

}

}

});

// Now you have a rendered report!

I don’t think it would be hard to add another report model type. All you have to do is follow the pattern already established in the first few lines:

var renderers = new Dictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer>

{

[typeof(StringReportModel)] = new StringReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(DoubleReportModel)] = new DoubleReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(TableReportModel)] = new TableReportModelRenderer(),

[typeof(NewfangledReportModel)] = new NewfangledReportModelRenderer() // Look, ma! A newfangled thingamajig

};

There are other ways to encapsulate this pattern. You could decorate the

renderers with attributes pointing out which model types they support, then

dynamically reflect over your assembly and get the

IReadOnlyDictionary<Type, ISpecificReportRenderer> from IoC.

It’s easy, flexible, extensible, SOLID, etc.

Marker interfaces aren’t intended for type-system safety

The author of the article rightly points out that

Since a marker interface is a contract [that] requires no behavior, [it] can never provide type-safety.

In response I say: then don’t use marker interfaces for type safety. Instead, use them to categorize types and reveal intent.

Marker interfaces are not evil

- They enhance the understandability and maintainability of your code

- They are useful when you have to hide the real behaviors of your system

- They are useful when C#’s type system forces you into unpleasant things like reflection and casting

- They can be easy to extend correctly

Use them! Use libraries that use them!